Backyard History: Message in a molasses barrel

After a storm cut communication to the mainland, the islanders of Iles de la Madeleine got an idea to contact the outside world: a molasses barrel full of letters to launch, then wait

Article content

In the winter of 1910 the isolated Iles de la Madeline’s undersea telegraph line – their only contact with the rest of Canada – was severed in a storm. They re-established contact with a message in a molasses barrel, called a ponchon.

If you draw a straight line between P.E.I. and Newfoundland, right in the middle you would find the isolated, fog-shrouded, and windy archipelago that is Iles de la Madeleine (also known as the Magdalen Islands in English, and Menagoesenog in Mi’kmawi’simk).

In 1910, the seven inhabited islands comprising the Iles de la Madeleine, which are connected by long sand dunes, were home to an estimated 6,000 people. These included immigrants from faraway Scotland, Ireland, and France, but were mainly Maritimers who were moving there to fish lobster.

Since they were so isolated, the Madilinots relied on a lone undersea telegraph cable, laid in 1882 by the federal government, to allow them access to news, allow families to keep in touch, and for merchants to contact suppliers.

On Jan. 2, 1910, a severe winter storm severed that telegraph cable, isolating the islands.

The Madeleinots waited for a sign from Canada’s government that their only connection with the mainland was going to be restored. And they waited.

One month later, with no sign of help coming, an islands-wide meeting was called to figure out what they should.

Have you heard of messages in bottles? Well, they decided to send a message in a barrel to the mainland. More specifically, a message in a ponchon, which was a large wooden barrel much more commonly used to transport molasses.

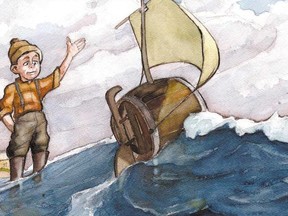

This was no ordinary molasses barrel though. It would take a custom deluxe ponchon boasting a sheet metal sail and an iron mast to make the 96-kilometre trip to Cape Breton.

Charles Boudreau recalled in an interview, much later in 1964, the most difficult part of constructing the ponchon was the rudder.

“It was impossible to attach a rudder made of wood like we had on all out other boats; the sea and the water would get into the ponchon by the holes from the nails … a five-foot long piece of iron from the railway … was the thing that worked best – it worked as a rudder and a keel and a ballast all at the same time that held the front of the ponchon up out of the water (just like a sailing ship),” he said.

On the sail made out of sheet metal were painted the words: “WINTER MAGDALEN MAIL.”

Boudreau explained, “We put it in English because if ever that ponchon made land it would certainly be land inhabited by the English.”

Inside the ponchon were 125 sealed cans, each containing a letter.

One letter, written by Georges Savage to his father on the mainland, began: ”I am writing you this letter, but I can’t tell you if you’ll receive it because it is being sent in a ponchon. The cable is broken and there is no way to send the news, so we thought of trying this.”

His letter included an order of lobster fishing supplies he would need before the season began.

Just before the ponchon was launched, Vergine Chevrier Painchaud wrote in a letter: “The contraption is ready: a barrel sailing, equipped with an iron rudder … held with hope that it will hold its ship in position so that it reaches somewhere. Our letters are sealed and waterproof. … At 2 o’clock this afternoon, the launch of this ‘fantastic vessel’ will take place … the wind is favourable and blessed be the one who will first come to the rescue of our frail vessel.”

The launch date was Feb. 2. Before Groundhog Day took over in popularity that date was Le Chandeleur (Candlemas in English), a holiday which involved eating a lot of crepes. (The tradition was to hold a coin in your right hand and a frying pan in your left. If you can flip the crepe and land it in the pan single-handed while holding the coin you would have good luck in the coming year.)

In the afternoon of Feb. 2, hundreds of Madelinots gathered on the beach outside the little fishing village of Havre-Albert. With great ceremony and high hopes, the ponchon was taken into the sea and released … and it promptly flipped over. It was too top-heavy, and its weight was unevenly distributed.

Most Madilinots went home to flip crepes. A few remained to tinker with the ponchon on the cold, wet, icy beach.

The sun had almost set by the time the frail little ponchon was finally launched into the sea. The wind caught its thin sail and it bobbed off into the darkness.

Everyone returned to their homes for their Chaldeleur crepes without a great deal of hope that their little ponchon would make it.

Ten days later, on Feb. 12, a Cape Bretoner walking along a beach spotted an unusual sight.

Imagine being this Cape Bretoner. You’re out for a walk along a beach and suddenly you find this frankly ridiculous-looking giant molasses barrel welded into a massive metal sailing ship with a five-foot-long iron rudder made from a railway tie.

You open it up and inside it is filled with 125 sealed tin cans, each containing a letter in a strange foreign language.

What would you do?

What the Cape Bretoner did was unseal all 125 cans and took out the letters. He brought them to the post office, personally paying the not-insignificant postage fee of one-penny-per-letter himself to mail the letters. It would have set him back nearly $200 in today’s money.

It was only when the 125 letters were being processed in Halifax two days later – on Valentine’s Day – that a postal worker finally began asking questions.

The alarm was raised, and only then, six weeks after communication had been severed, that the government noticed that they were missing 6,000 Canadian citizens.

The Cape Bretoner was sent $30 by the grateful Madilinots (a few thousand dollars in today’s money) showing that generous acts of kindness really do pay off.

Andrew MacLean is the author of Backyard History: Forgotten Stories From Atlantic Canada’s Past, available at backyardhistory.ca/shop.

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.